House was “complete embodiment of everything a charming home should be”

On April 4, 1922, the Winnipeg Evening Tribune ran a short story on page 6 under the headline “To Heat Houses By Electricity” that almost seemed inconsequential at the time.

It was a story about Francis William Cumming, and what we now know as his small part in making electricity an everyday part of our lives.

A century ago, Winnipeg boasted the lowest electric rates in Canada at three cents a kilowatt hour. Today, it’s 8.9 cents and we still have the lowest rates in Canada. Why? Hydro power. And Cumming saw that.

Back in 1922, Cumming and others saw the future of affordable, abundant electricity and what it meant for Winnipeg’s growth and prosperity. And making the lives of its citizens and business so much easier.

Cumming worked full-time as an accountant in Winnipeg’s powerful grain trade, but on that spring day in 1922 day he did something never done before in Winnipeg.

Newspaper ad for Western Terminal Elevator Company (Winnipeg Evening Tribune 1915).

Enlarge image: Western Terminal Elevator Company newspaper 1915 ad.

On behalf of the Electrical Home Construction Company, Cumming took out a $7,500 building permit to build the first all-electric house in Winnipeg, located on the west side of Niagara St. between Wellington Cr. and Academy Rd. in River Heights. The value of the building permit indicated it would be no ordinary house — $7,500 is equal to about $117,500 today.

Cumming, secretary-treasurer of the Western Terminal Elevator Company (now Richardson Pioneer), told the Winnipeg Evening Tribune that the house would be the first of about 30 homes the Electrical Home Construction Company planned to build in River Heights to be heated by electricity, which was then supplied by generating stations on the Winnipeg River.

The house at 129 Niagara St. was to be constructed and owned by building company Brown & Matthews, and intended to be “a well-planned, well-built, well-furnished, completely wired modern home,” according to the Evening Tribune in a following story.

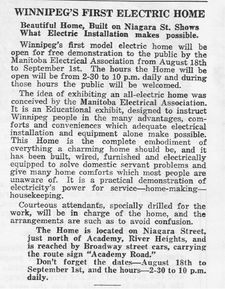

Winnipeg’s first electrical home (Winnipeg Evening Tribune 1923).

Enlarge image: Illustration of Winnipeg’s first electrical home from 1923 newspaper story.

And Cumming could watch it being built daily – he lived nearby at 114 Niagara St.

Some perspective is needed. One hundred years ago, electricity in the home was a novelty, but that was quickly changing because of people like Cumming. The champions of electricity said cheap power from water advocated it would propel Winnipeg into a new era of prosperity following the First World War – it would herald more business, more people, and more growth.

Called the ‘Electrical City’ by Winnipeg Hydro, the rapidly growing city would also have the lowest rates in Canada – the electric light rate was three cents per kilowatt hour.

Winnipeg: The Electrical City

In the ’50s, plentiful electricity was one of the main selling features of life in Winnipeg. Here’s an old ad from City Hydro pitching the various amenities “The Electrical City” had to offer.

To drive this growth, Winnipeg Hydro’s Pointe du Bois Generating Station had recently started supplying power to it citizens and the utility was in the early planning stages of the Slave Falls Generating Station. Meanwhile, the Winnipeg Electric Railway Company (WERCo) – which ran the city’s streetcars — had been operating its Pinawa Generating Station for several years and was building the Great Falls Generating Station.

Winnipeg Electric Railway Company brochure for Great Falls Generating Station, completed in 1928.

“If Winnipeg has been prosperous in the past, no great amount of prophecy is required to predict the era of prosperity that awaits her in the immediate future,” trumpeted Winnipeg Hydro in a full-page October 1922 newspaper advertisement. “Winnipeg MUST advance.”

The house at 129 Niagara St. was a symbol of Winnipeg’s bright future and the convenience of affordable hydroelectricity. Not many other details about the house were mentioned in the Evening Tribune in 1922, other than it would be built of frame and stucco on a stone foundation 24 feet by 34 feet (816 square feet) with a peaked and shingled roof.

The next mention of the house in the Evening Tribune appeared on the front-page June 1, 1923 under the headline “Pays $214 Bill For Wired Heat.”

The short article said it cost Cumming, as the permit holder, $214.15 for electrical energy to heat the home September 22, 1922 to March 21, 1923. ($214 in 1922 is equivalent to about $3,300 today).

“The consumption over this period was 29,500-kilowatt hours and the load for the first part of the winter was 10 kilowatts and 12 kilowatts for the latter part,” the Evening Tribune said.

Several other newly built homes in Winnipeg were also heated by electricity that year: three houses on the 200 block of Waterloo St. in River Heights and a house on St. John’s Ave. in the city’s north end.

Promotional article for tour of first electric home in the Winnipeg Electric Railway Company’s August 15, 1923 Public Service News.

Enlarge image: News story advertising public tours for Winnipeg’s first electric home.

But it was the city’s first electric home at 129 Niagara St. that was the showcase for Winnipeggers.

Streetcar riders were encouraged to tour the Model Electric Home and see the marvels of electricity themselves August 18 to September 1, 1923, a tour hosted by “courteous attendants.”

“It is an Educational exhibit, designed to instruct Winnipeg people in the many advantages, comforts and conveniences which adequate electrical installation and equipment alone make possible,” according to a write-up in WERCo’s Public Service News, a free bulletin available on streetcars.

“This Home is the complete embodiment of everything a charming home should be, and it has been built, wired, furnished and electrically equipped to solve domestic servant problems and give many home comforts which most people are unaware of,” the write-up said. “It is a practical demonstration of electricity’s power for service – homemaking – housekeeping.”

The house on Niagara St. was mentioned again in the Tribune on August 23, 1923 when the paper reported an average of 1,700 people a day had toured it since the open house started. Because of the crush of people, the Manitoba Electrical Association urged people to tour it in the late afternoon to avoid the evening rush.

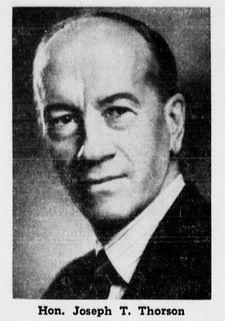

Little is mentioned about 129 Niagara St. again. Its first long-time residential owner was Winnipeg lawyer Joseph T. Thorson, who’s listed as the owner in the 1924 Henderson’s Directory. Thorson was the Liberal MP Winnipeg South Centre (1926–30) and Selkirk (1935–42). From 1941 to 1942, he was the Minister of National War Services in the cabinet of William Lyon Mackenzie King. In 1942, he was made President of the Exchequer Court of Canada. He died in Ottawa in 1978 at age 89.

Joseph Thorson, lawyer and politician (The Manitoban 1958).

The house at 129 Niagara St. is now owned by civil engineer David Haines, who moved into the property about one year ago. A previous owner converted it to natural gas heating.

Haines said he was unaware of his home’s history – until now.

“It’s wonderful to learn the history of my home and part it played in the city’s history,” he said. “Much of the original character of the house has been preserved.”

And Cumming? The 69-year-old member of the Winnipeg Grain Exchange died at his house December 6, 1931 and is buried at Elmwood Cemetery.

The property at 114 Niagara St. is now owned by Dr. Scott Leckie, who bought the house in 1993.

Leckie said the original home’s stone foundation had shifted significantly over the years due to a large elm tree in the front yard (since removed because of Dutch Elm Disease) — so much so the front door would not close properly.

Leckie said he explored replacing the original home’s foundation and putting in new footings, but the cost was substantial.

He said in the end his family decided to demolish the house and rebuild in 2019 with a modern, energy-efficient home, much like the house Cumming was responsible for building down the street in 1922.